In the autumn of 2023, we held a series of seminars to review aspects of the work in Christian-Jewish dialogue and theological reflection of the Roman Catholic, Anglican, and Lutheran churches, considering how the process and shape of this work may inform our own Orthodox Christian consideration of similar issues and themes.

We began our series with a discussion of the Church of England’s God’s Unfailing Word: Theological and Christian Perspectives of Jewish Christian Relations.

Professor Emeritus of Wycliffe College, University of Toronto, Rev Dr Ephraim Radner presented the document, its history and main ideas within the broader context of the development of attitudes towards Jews and Judaism in the theology, pastoral practice and worship of the Anglican Church — starting from open antisemitism (“Jews are degrading Christian culture of England”), through “philosemitic evangelism” (proselytising activity, conversion of Jews), to revising negative images of Jews in church teaching and liturgy and accepting Jewish-Christian relations as a mystery that can be resolved only in the age to come.

Dr Radner described what the document sets out as four “approaches” or “theological frameworks” of the relations between Judaism and Christianity reflecting various positions within the Church of England. These capture stages of historical development in the church’s Jewish mission and relations. In the emerging preferred view, the Church of England accepts as undeniable the “continuing participation of the Jewish people in Israel as God’s gift and God’s creation” and that “there is a mystery here that transcends its understanding in history.” This approach has already influenced changes in the language of worship as well as further theological reflection, informed by the questions that are posed throughout the document.

In our ensuing discussion, the key questions raised centred on Christian identity in relation to Israel, Jews, and Judaism. How do we identify ourselves? Are we Christians, distinct from Judaism and Jews, who are simply struggling to conquer antisemitism and exhibit openness and love towards Jews? Or is the relationship deeper and more fundamental? What does it mean for the church to be Israel, participating in God’s covenant with Israel? How do we construe the mystery of that shared covenant with the ongoing Judaism — as something we just can’t puzzle out or understand for now, or as a true mystery in the sense of paradox in which both claims to being “Israel” are true? And who then are Jews for us — “we” or “they”?

These are questions we will continue to reflect on in our upcoming working seminars.

In our second seminar, we reviewed Preaching and Teaching “With Love and Respect for the Jewish People,” published by the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America after many years of discussion of anti-Jewish aspects of Lutheran theology, liturgy and pastoral practice as “a tragic contributor to the wider Western cultural antisemitism of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.” This practical guide aims to provide a new vision for teaching and preaching about Jewish tradition and its significance. Leading our discussion was the Rev Dr Peter Pettit, Lutheran minister and teaching pastor at St Paul Lutheran Church in Davenport, Iowa, who led the ELCA Consultative Panel on Lutheran-Jewish Relations which authored the document.

If our first seminar centred around issues of Christian identity in relation to Jews, Judaism, and God’s Covenant with Israel, the main questions of this encounter were more practical, addressing the problem of framing the “newness” of Jesus and Christianity by contrasting these with his Jewish tradition and context (for instance, “Since Jesus is the light of the world, Jews are portrayed as being in the dark”).

Dr Pettit showed how this document creates a system of counterbalances to this language, primarily through historical-critical and biblical studies. He emphasised unbiased studies of Scriptural texts, particularly St Paul who needs to be read “before Augustine and Luther,” as well as the necessity to avoid anachronisms “between the time of Jesus and the New Testament writings, between the first century and 21st century.” Thereby Jesus can be understood as “a Jew within Judaism, not terminating it,” keeping “Torah as a lifestyle,” and not contrasting himself with Israel, but rather offering a prophetic word and challenge in the same vein as Jewish prophets had before him. Dr Pettit described how the guide revises the traditional Lutheran confessional reading of Paul: Luther used Paul to oppose the pope, while Paul himself never “opposed Judaism with Jesus,” instead criticising it from within, using its own language; it is an intra-Jewish discussion to which the nations are invited. Dr Pettit also demonstrated how the document reinterprets other key concepts of Lutheran theology around law and grace, promise and fulfilment, on which anti-Judaic theological discourse has relied for centuries.

By carefully rereading the New Testament and early Christian tradition and reframing theological presuppositions based upon that tradition, the document is able to make informed recommendations for renewed teaching and pastoral practice. It has even begun to influence a new, historically-sensitive translation of the Revised Common Lectionary used in a number of western churches, called “Reading from the Roots.” In the Biblically-grounded and careful historical work of this document, there is no doubt a model for our working group’s review and renewal of Orthodox theology and practice on similar issues.

In our third seminar, Dr Gavin D’Costa led us in a review of documents from Catholic-Jewish encounter and dialogue, including the watershed Nostra Aetate, a section from Lumen Gentium providing ecclesiological context to Nostra Aetate, and the 2015 document, “A Reflection on Theological Questions Pertaining to Catholic-Jewish Relations on the Occasion of the 50th Anniversary of Nostra Aetate.”

Dr D’Costa is Professor of Catholic Theology at the University of Bristol, an advisor of the Pontifical Council for Other Faiths, and the author of two recent books on Catholic doctrines about Jewish people, Vatican II: Catholic Doctrines on Jews and Muslims (2014), as well as Catholic Doctrines on the Jewish People After Vatican II (2019). Responding to Dr D’Costa was Rabbi Mark Kinzer, a founder of Yachad BeYeshua International Fellowship of Jewish Disciples of Jesus, Senior Scholar and President Emeritus of Messianic Jewish Theological Institute, the author of the monograph, Searching Her Own Mystery: Nostra Aetate, the Jewish People and the Identity of the Church (2015).

Dr D’Costa explained by background of Nostra Aetate, beginning with the proposal of Jules Isaac in dialogue with Cardinal Bea to revisit theologically the deicide charge that for centuries created a justification for legalised antisemitism in the Church. The resulting Catholic documents on relations with Jews and Judaism weren’t an attempt to change doctrine, but rather set out to articulate a “doctrinal position” emerging from an unbiased interpretation of Biblical sources and a critical re-thinking of ecclesiology. The reconsideration is expressed in the statement of Lumen Gentium 16, recognising the exceptional role of Jewish people in the history of salvation: “the people to whom the testament and the promises were given and from whom Christ was born according to the flesh. On account of their fathers this people remains most dear to God, for God does not repent of the gifts He makes nor of the calls He issues.”

Overturning a centuries-old popular assumption that Jews knowingly rejected Christ, this document along with Nostra Aetate states that Jewish people, even those “who have not received the Gospel,” relate to God in Christ in a very special way. A key word here is “relate,” Dr D’Costa stressed; these relations have never been terminated, they extend into eternity. Nostra Aetate provides an expanded theological refutation of the deicide charge, although it doesn’t use the word “deicide”. Dr D’Costa described sections of the document “as a very delicate dance” that both acknowledges that certain Jewish people “were involved in putting Jesus to death” and the same time clearly says that “not all Jews at that time or subsequently can be blamed for this event.”

The 2015 document written on the occasion of the 50th anniversary of Nostra Aetate further suggests that the “replacement theology” originating in certain patristic texts and developed in later mediaeval theology, does not rest on solid theological foundations and cannot be taught as a Biblical truth. Such a radical turn from supersessionist theology to the new understanding of the election of Israel, based on God’s absolute faithfulness to his people, has had two important implications. First, it has encouraged a positive movement towards Jews and Judaism in contemporary Catholic theology.

The second implication, not so evident for many, but clarified by Dr Kinzer, is a deeper understanding of the spiritual ties between “the people of the New Covenant” and descendants of Abraham. It means that the “very roots of the Church are Jewish,” and the heart of the Gospel is Jewish revelation; the Church began and remains in essence “a Jewish Messianic movement that integrated Gentiles into the Jewish Covenant.” This completely changes the trajectory of the Jewish-Christian dialogue: it becomes a profound relationship “with genuine others as ourselves, existing in the same continuity of the Covenant.” Connected with this Jewish nature of the Church is the new question of Jewish (Hebrew) Catholics as well as Orthodox, who are united with “Abraham’s stock” not only spiritually, but genealogically.

This brought the discussion back to the question of Christian identity: who we are in relation to Judaism? If we are heirs of the same Covenant, antisemitism isn’t just a social or political evil, but a heresy, denying the concreteness of Incarnation. However the Jewish roots of the Church can’t be taken taken for granted. This theological claim demands significant educational efforts, first of all careful studying the whole history of Jewish thought from Biblical and Rabbinic Judaism to contemporary spiritual movements and witnesses.

The critical reflection on the personal witnesses and theological legacy of Jewish Christians and key figures of the Jewish-Christian dialogue will be the core of our spring seminars.

In the next phase of our consultations, we are giving critical consideration to the contributions and legacy of key figures in Christian-Jewish dialogue over the last century.

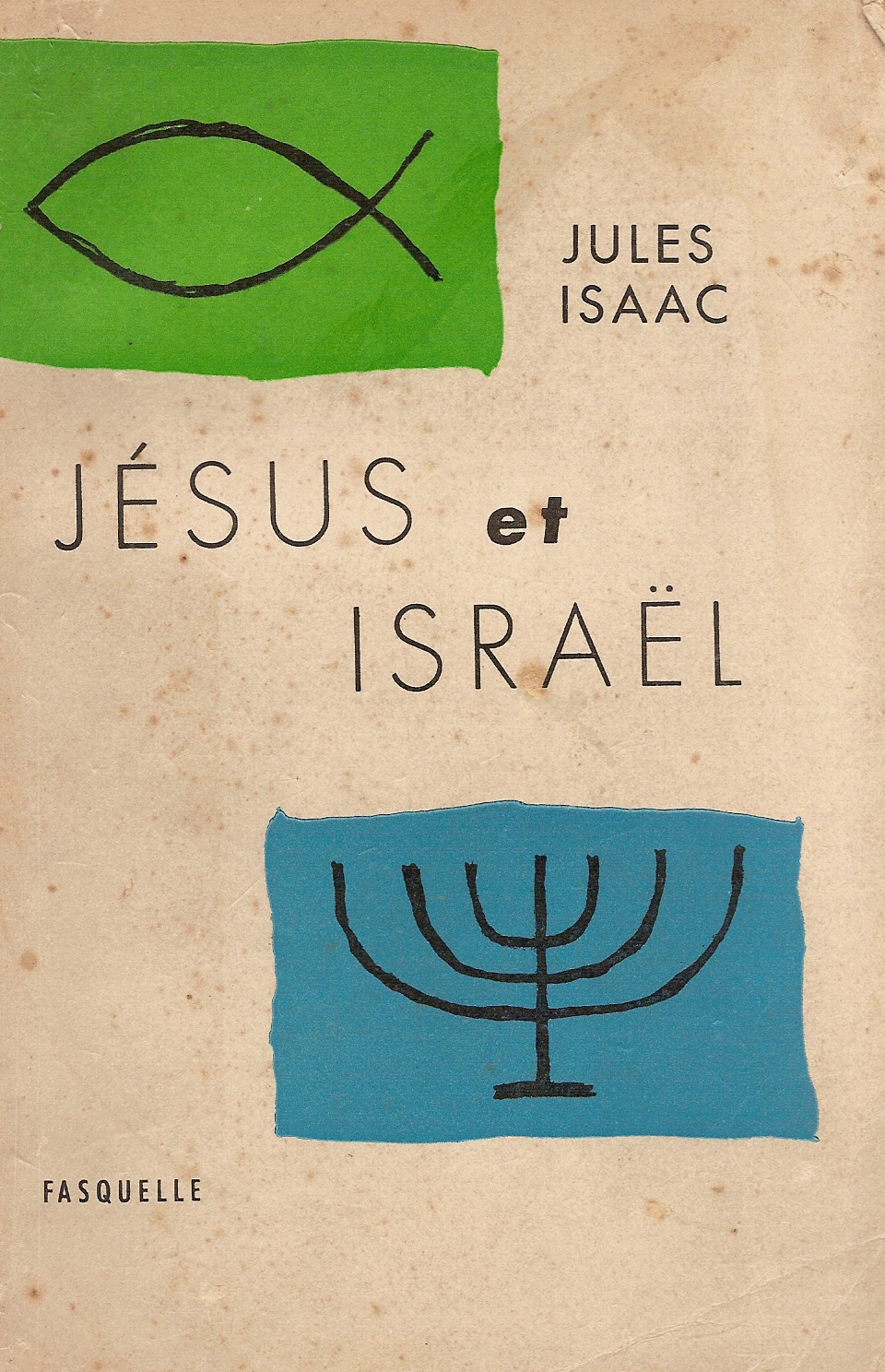

In the first in a series of reflections about key figures in the history of Jewish-Christian relations in the 20th century, we reviewed the intellectual and spiritual legacy of Jules Isaac (1877-1963), who played a decisive role in the reconsideration of Jewish-Christian relations after World War II. The discussion was led by Dr Norman Tobias, author of the profound intellectual biography of Jules Isaac, Jewish Conscience and the Church: Jules Isaac and the Second Vatican Council, published in 2017.

Jules Isaac wasn’t a professional theologian or religion scholar. He was a historian, one of the most authoritative educators in pre-war France. A co-author and editor of French and world history texts widely used in all French secondary schools, a friend of one of the most significant French poets and Christian thinkers of 20th century, “a prophet of a renewed Catholicism” Charles Péguy, a renowned scholar, Jules Isaac, as many his contemporary French intellectuals of Jewish origin, never denying his roots considered himself part of European culture, and believed that, as Dr Tobias put it, “the service for the Republic is the best fulfilment of Jewish identity.”

Isaac’s father and grandfather were officers of the French Army and holders of the Legion of Honour. He was one of those “recognised Jews” to whom, after the Nazi occupation of France in 1940, “state protection” was promised, however, these were empty promises. In the same year, he lost his position in the French school system, for as a Jew he had no right to teach publicly. In 1941 together with his wife and the youngest of his two sons, he took refuge in a “free zone” in Aix-en-Provence. From that time they had to flee from one hiding place to the next to avoid arrest.

In 1943 his wife and children were caught during a raid. Jules Isaac tried unsuccessfully to save them. Soon after being arrested, his wife managed to send him a note: “My friend, take care of yourself, have confidence, and finish your work. The world is waiting for it.” The “work” in question was research in a new field: a history of anti-Jewish trends in Christian theological thought.

As Dr Norman Tobias convincingly showed, Isaac responded to this tragedy in his characteristic way, as a scholar: Jewish solidarity with “hated, slandered, scorned Israel” encouraged him to research the sources of the unfair condemnations of Jews in the Christian tradition. Already in 1942 with the help of befriended pastors and priests, who provided him with the necessary books, he began to study classical Christian sources on Jews. “In search of the historical roots of antisemitism that was afflicting him, and suspicious” that Jesus’s universalism was distorted by later church teaching, Jules Isaac started to read the New Testament. He read it in Greek to escape distortions made in the later translations.

After the arrest of his family, this study of Christian teaching about Judaism became for Jules Isaac, as Dr Tobias described it, “a sacred cause.” In 1948 the 600-page book Jésus et Israël was published. In the words of Dr Tobias, it was “the first sustained, well-grounded, and passionately argued intellectual assault on anti-Judaism in history.” It became a cornerstone for the post-war theological reconsideration of the relationship between the church and the Jewish people, resulting in the Nostra Aetate declaration at the Second Vatican Council, and subsequent church documents. Twenty-one points of the “rectification necessary in Christian teaching” articulated in this book became the basis of the document known as “Ten Points of Seelisberg,” adopted in 1947 at the International Emergency Conference of Christians and Jews at Seelisberg, Switzerland. These principles laid the foundations for subsequent Jewish-Christian discourse in western churches.

Describing Jules Isaac’s theological position, Dr Tobias started with the notion of a “discovery” – as Isaac himself described it – that “a received tradition regarding Jesus in relation to Israel and Israel in relation to Jesus, a tradition that impacted upon Christian faith and doctrine, became a primary and permanent source for antisemitism.” It is that tradition which introduced in the Christian mind the idea of the “collective responsibility of Jews for deicide,” and generated a sort of “custom of prejudices.” This thesis of Isaac’s elicited both sympathy and resistance among French Catholic intellectuals. Nevertheless, it raised for the first time the question of the Christian theological and pastoral responsibility for Holocaust, which became a one of the foundations for post-Holocaust theology. It was Isaac who ensured the issue was placed on the agenda of the Second Vatican Council.

The essence of Jules Isaac’s new theological vision, Dr Tobias stated, is that the “God of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob abides and never ceases to abide in the covenantal relationship with the Jewish people.” That means that the church has no rationale for stating that Jews are denied election or grace, or that “old Israel” is substituted by a “new” one, or for seeking to convert Jews. New post-Holocaust hermeneutics, “solidly grounded in ideas of Jules Isaac,” as Dr Tobias emphasised, requires a recognition that “Judaism remains a dispensation of grace, and Christians should instead of trying to convert Jews, engage in dialogue with them.”

The notion of “discovery” was a centre of the discussion that followed the presentation. The position of “non-professional theologian” allowed Jules Isaac to submit his thought completely to a transformative process of simply “seeking truth”. Dr Tobias added that as a historian Jules Isaac had been suspicious of official French historiography, particularly around the causes and aftermath of World War I. The same “methodology of suspicion” he adopted towards those events informed his comparative reading of New Testament in Greek and Christian patristics, and finally brought him to conclusions that couldn’t be achieved by the “thinking by custom.”

As for Jules Isaac’s acquaintance with Orthodox Christian theology, Norman Tobias explained that, besides direct family connections (Jules Isaac’s granddaughter Marie-Claire married Fr Michel Evdokimov, the son of Orthodox theologian Paul Evdokimov), he stayed in dialogue with Léon Zander (professor of theology at the Orthodox Institut Saint-Serge in Paris) as well as with the Orthodox who joined Amitié Judéo-Chrétienne de France (AJCF), initiated by Jules Isaac in 1948. Zander’s response to Isaac’s Jésus et Israël in the transcription of a radio discussion appeared in the first issue of the AJCF’s magazine in September 1948.

Led by Rev Dr John Jillions, we reviewed the work and legacy of Father Lev Gillet (1893-1980), the French Orthodox Christian priest whose prophetic book Communion in the Messiah, written in 1941, presents ongoing theological and ecclesiological challenges.

Fr John presented an overview of Fr Lev Gillet’s spiritual journey from Catholicism of the Eastern Rite to Orthodoxy, paying special attention to the development of his theological thought as presented by Gillet’s seminal book Communion with Messiah. Published at a time when the Nazis were implementing their “final solution of the Jewish question,” this book became both a form of theological protest against the extermination of the people of the covenant, and the one of the first studies of the challenging relationship between Judaism and Christianity from within the perspective of 20th century Orthodox theology.

Fr John outlined the pastoral position of Fr Lev Gillet, his vision of the church, not as an institution but as heir to the same covenant, constantly renewed by the revelation of the Holy Spirit. It was Gillet’s spiritual sensitivity that brought him to the idea of communion between Jews and Christians in Messiah. This idea continues to challenge two influential Christian approaches to the relationship with Judaism: (1) the one-sided “mission to the Jews” animated by a Christian sense of superiority, as well as (2) formally-constituted dialogues lacking any genuine attempt to understand the meaning and complexity of the deep theological connection between Christianity and Judaism.

Fr John recalled one of Gillet’s main insights, that for an authentic meeting with its “older sister synagogue,” the church should enter into the dialogue as a humble disciple with readiness to learn from the Jews, to recognise and to correct its own misconceptions, in the first instance about Rabbinic Judaism and Jewish thought. Fr Gillet pointed not only to the spiritual value of Judaism, but also to its development over the centuries, arguing that viewing Judaism as “stagnant” is not only an obstacle for dialogue, but frequently serves to justify supersessionist teaching.

Discussion focused on the teaching about shared Christian and Jewish communion in the messiah, as well as the place for Jewish followers of Jesus within the church without rejection of their Judaism. This was modelled in the pastoral practice of Fr Lev Gillet: from archival correspondence it is known that he performed memorial services for non-baptised Jews who believe in Jesus, including the wife of St Ilya (Fondaminsky) who attended Gillet’s Paris church. Biographers of Simone Weil also mention that he came to pray for her when she died. These accounts, as well as the text mentioned by some of his contemporaries that Gillet had written as a special service for non-baptised Jews, could be a helpful avenue of research. The biggest difficulty, Fr John noted, would be finding any authentic texts, because Gillet didn’t keep his archives.

The participants of the seminar agreed that, though Fr Lev Gillet is widely known in the Orthodox world as a “Monk of the Eastern Church,” author of popular books on Orthodox spirituality, it is his profound reflection on the relationship with Judaism that demands comprehensive theological research in order to enrich our understanding of the boundaries and possibilities of dialogue between Orthodox Christianity and Judaism.

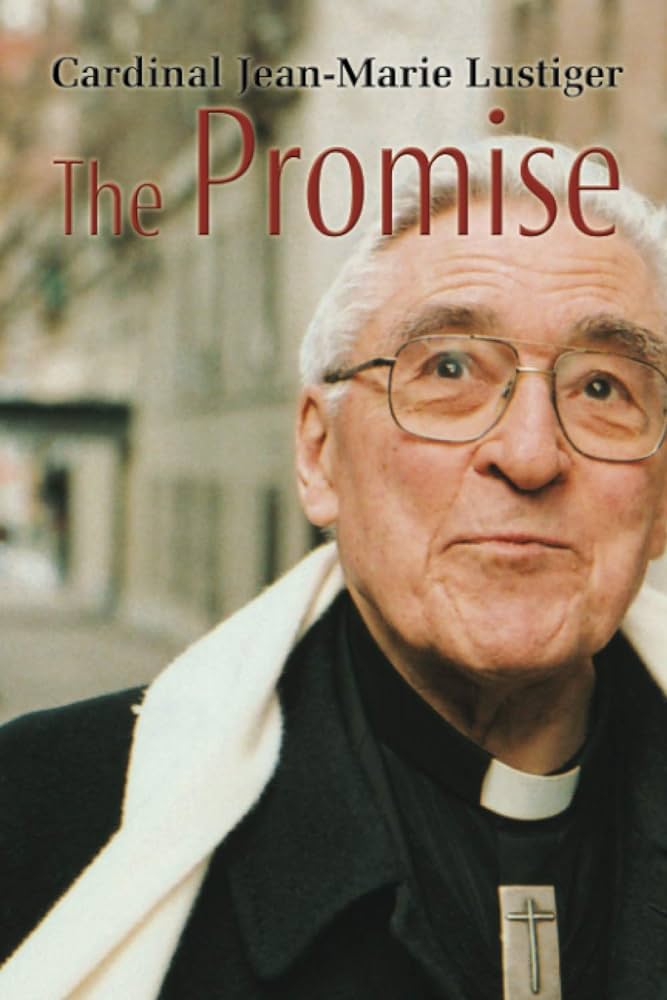

Led by Dr Rivka Karplus, based in Jerusalem and translator of La Promesse into Hebrew, we reviewed the work and legacy of Cardinal Aron Jean-Marie Lustiger (1926-2007), the “Jewish Cardinal,” whose determination to hold to his Jewish identity as a follower of Jesus has profoundly influenced theological reflection on the Jewish heart of the Christian Church.

Dr Karplus spoke about the most important moments and themes of Cardinal Lustiger’s theology in the wider context of his life, actions, and personal commitments. The talk was centered around the texts included within La Promesse (The Promise), a book on Jewish-Christian themes based on a retreat Lustiger led in 1979 at the Benedictine Convent of Sainte Franҫoise Romaine in France as well as at conferences given in Jewish contexts. As Rivka Karplus stressed, this book “isn’t his personal story but you can hear his prayerful reading of the Scripture.”

The presentation was built on the parallels between Lustiger’s biography and his theological insights. Dr Karplus noted that Aron Lustiger was born on Yom Kippur 1926, and that became an important calendar symbol for him, not least St Edith Stein, a powerful figure for him, was born on Kippur. He was brought up as Jewish and French, determining both his faithfulness to the Jewish identity, including responsibility for ethical actions, as well as openness to the “values of the Republic.” At the same time, antisemitism was part of his life from the very early years. His first close encounter with Christians was a meeting with Susanne Combe, to whom he was entrusted by parents in 1939. In his words, she was a “living exposure of what she believed,” though she never imposed her beliefs on anyone. Aron Lustiger decided to be baptised without any external influence, “in a very classic Lustiger” manner: reading the Old and New Testaments as a continuity (“they deal with the same spiritual subject, the same blessing and the same stakes: salvation of mankind, the love of God…”). Throughout his life this continuity between Judaism and Christianity would become a central theme of his theology. It was founded on the firm conviction that God is present in the tradition of his people. Surviving the Shoah, though his mother was deported to Auschwitz and murdered there, was another powerful experience that would echo in his teaching and preaching throughout his life.

Having set out a biographical framework as a commentary to Lustiger’s Jewish Christian theology, Dr Karplus highlighted some of its key themes. There is the “mystery of Israel,” continuity and fulfillment – “If Christianity tries to separate itself from Judaism, it ceases to be itself… God’s promise is fulfilled in Jesus the Messiah” – antisemitism in the Church, understanding the catholicity of the Church as the inclusion of both Jewish and Christian elements, “testifying to each other and together testifying about God’s grace.” Another fascinating but often overlooked theme is the discussion of Jesus and Torah, and the meaning of mitzvot for non-Jewish Church members. The main theological starting point for him, Dr Karplus contended, was the essential Jewishness of Jesus “that closely touches the essence of the Christian Church.”

A part of his personal commitment and theology was an attempt to explain what it means to be Jewish and at the same time a Christian: “It is as if suddenly crucifixes started to wear the yellow star of David.” Cardinal Lustiger was among the first in the Catholic church to speak about it overtly. For him it wasn’t a theological statement, but an issue of his double identity, double faithfulness to the nation and to the truth: “I can’t repudiate my Jewish condition without losing my own dignity… I respect this truth and what is due to the truth.” He was a man of the oral word, and in most cases, he didn’t write his sermons, but preached based on the Biblical text and the context of the concrete situation or audience. In fact, it was a very Jewish form of preaching, a midrash, born from the encounter of the Biblical text with the life situation.

It could be said that Cardinal Lustiger tried to create and introduce this language of double identity as an integral part of the Jewish-Christian discourse. This language helped him to move from the formal respectfulness to the close relations with Jewish communities, expressed by the question: “How can we study together?” It was a clear message to the Church; for starting a dialogue with Judaism, we need to know it and its exegetical tradition.

Dr Karplus showed that Cardinal Lustiger’s Jewish Christian theology and language are of prophetic nature. They raise a lot of painful questions, and are sometimes too provocative, but they bring the church back to its real nature, inseparable from its Jewish roots. Born on Yom Kippur and dying on the Feast of Transfiguration, the “Jewish Cardinal” revealed this nature in his own life and intellectual legacy, both of which should be read as a profound theological reflection on the mystery of the church and “on the entire history of the people of God.”

Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews is a project and working group of the Orthodox Theological Society in America (OTSA).

For more information please contact info@ocdj.net

Header image: Marc Chagall’s Peace Window at the United Nations

Sign up for the monthly newsletter of the Orthodox Theological Society in America.

To receive regular updates from Orthodox Christians in Dialogue with Jews, please complete the expression of interest form.